Revealing the nature of a diffuse Lyman-alpha glow around galaxies

Recently, astronomers discovered an extended glow of emission far beyond the stellar bodies of galaxies. While the emission is known to be associated with excited neutral hydrogen, the origin of this so called Lyman-alpha radiation is unknown. MPA researchers use new computational models to understand this emission, establishing that a large contribution is caused by light which originates from deep within galaxies but subsequently scatters at much larger distances.

Hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe, emits ultraviolet radiation through the so-called Lyman-alpha spectral line, when sufficiently excited. In the 1970s it was theorized that this Lyman-alpha line should shine brightly, especially in young galaxies, thus allowing astronomers to observe distant galaxies ten billion light-years away. Since then, the Lyman-alpha line has indeed been verified as a powerful observational tool to study galaxy formation and cosmology.

Lyman-alpha halo

Just in recent years, the sensitivity and spatial resolution of telescopes and satellites have become powerful enough to observe not just Lyman-alpha within the galaxies but also a faint extended Lyman-alpha glow surrounding them. This allows astronomers a glimpse of the gas that surrounds young galaxies that is of crucial importance for their future evolution. While more and more such observations become available, the source of this Lyman-alpha emission remains unknown.

There have been various hypotheses concerning the source of this glow. Generally speaking, there are two different types of possible mechanisms: On the one hand, the glow could stem from Lyman-alpha photons that are created in the star-forming regions within the galaxies and are subsequently scattered by the neutral hydrogen surrounding the galaxy. On the other hand, the diffuse Lyman-alpha emission could be created in the galaxy's surrounding gas. For example, gravitational cooling or small satellite galaxies could provide a significant energy source for such a diffuse glow.

Theoretical progress has been complicated by two factors: the Lyman-alpha line is resonant and in astrophysical settings, there is a high optical depth. This means that Lyman-alpha photons can scatter thousands or millions of times before a photon reaches us, making it impossible to know where the photon was originally emitted and what was its exact frequency. Given such physical complexity, numerical simulations of galaxy formation coupled to a radiative transfer code to account for photon scatterings are thus an important tool to study Lyman-alpha observations.

In the last years, various simulations have tried to explain the physical origin of Lyman-alpha emission around galaxies, also called Lyman-alpha halos. They performed explicit radiative transfer calculations that properly capture those effects such as scatterings and change in frequency. Detailed radiative transfer simulations can be run on top of cosmological hydrodynamical simulations, but previous studies could not do so on large scale. A statistically robust sample would require thousands of galaxies that are resolved down to just 100s of light-years, to match up with the manifold of observational data.

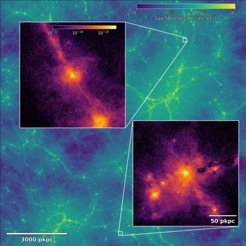

In a recent leap, researchers at MPA used the new high-resolution cosmological simulation TNG50 of the IllustrisTNG project and a new radiative transfer code called voroILTIS to determine the origin of the Lyman-alpha glow. The TNG50 simulation provides an unprecedented combination of volume and resolution, while the voroILTIS radiative transfer code includes models for the various Lyman-alpha emission sources mentioned above and explicitly follows virtual photons as they scatter their way towards an observer. This allows to statistically compare the simulation's predictions with existing Lyman-alpha halo observations, while also probing questions regarding the dominant origin and emission mechanism for Lyman-alpha halos.

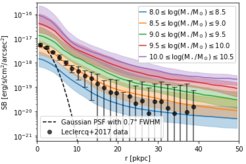

Comparison of stacked and individual Lyman-alpha radial profiles from those simulations with observational data from the MUSE Ultra Deep Field reveals a promising level of agreement. Those simulated radial profiles also allow a decomposition into contributions from inside the galaxy, i.e. scattered photons from star-forming regions, and outside, such as recombination from the ultraviolet background and collisional excitations powered by gravitational cooling. This decomposition suggests that the Lyman-alpha glow is dominantly powered by emission from star-forming regions for the majority of galaxies.

Multiple shortcomings in the computational model, such as the lack of a description of clumping hydrogen and dust below the resolution scale and the ionizing flux from local sources, remain to be resolved in upcoming work. Nevertheless, these findings allow multiple exciting opportunities for astronomers in the future: With the nature of the Lyman-alpha glow established, future work can decipher the information contained in the Lyman-alpha glow to deepen our understanding of the underlying gas that surrounds galaxies and shapes their evolution. The recent theoretical findings at MPA also suggest that the larg-scale structure, the cosmic web, within which those galaxies reside, can be observed via such Lyman-alpha glow in the near future.