Zooming in on Dark Matter

Computer simulation reveals similar structures for large and small dark matter halos

Most of the matter in the Universe is dark and thus not directly observable. In results just published in the journal Nature, an international research team harnessed supercomputers in China and Europe to zoom into a typical region of a virtual universe by a totally unprecedented factor, equivalent to that needed to recognise a flea on the surface of the full Moon. This allowed the team to make detailed pictures of hundreds of virtual dark matter haloes from the very largest to the very smallest expected in our Universe.

Dark matter plays an important role in cosmic evolution. Galaxies grew as gas cooled and condensed at the centre of enormous clumps of dark matter, so-called dark matter haloes. The haloes themselves separated from the overall expansion of the universe as a result of the gravitational pull of their own dark matter. Astronomers can infer the structure of big dark matter haloes from the properties of the galaxies and gas within them, but they have no information about haloes that might be too small to contain a galaxy.

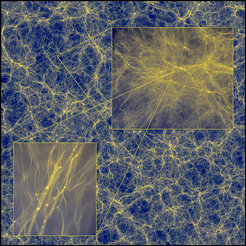

This image shows a slice through the main simulation which is more than two billion light years on a side. The two insets are successive zooms into regions which are 700 thousand and then just 600 light-years on a side. The largest individual lumps in the main image correspond to clusters of galaxies, while the smallest lumps in the second zoom are similar in mass to the Earth.

The biggest dark matter haloes in today's universe contain huge galaxy clusters, collections of hundreds of bright galaxies. Their properties are well studied, and they weigh over a quadrillion (1015) times as much as our Sun. On the other hand, the masses of the smallest dark matter haloes are unknown. The theory of dark matter that underlies the new supercomputer zoom suggests that they may be similar in mass to the Earth. Such small haloes would be extremely numerous, containing a substantial fraction of all the dark matter in the universe, but they would remain dark throughout cosmic history because stars and galaxies grow only in haloes at least a million times more massive than the Sun.

The research team, based in China, Germany, the UK and the USA took five years to develop, test and carry out their cosmic zoom. It enabled them to study the structure of dark matter haloes of all masses between that of the Earth and that of a big galaxy cluster. In numbers: The zoom covers a mass range of 10 to the power 30 (that is a 1 followed by 30 zeroes), which is equivalent to the number of kilograms in the Sun.

Surprisingly, the astrophysicists found all haloes to have very similar internal structures: They are very dense at the centre, becoming increasingly diffuse outwards, with smaller clumps orbiting in their outer regions. Without a scale-bar, it is almost impossible to tell an image of the dark matter halo of a massive galaxy from one of a halo with less than a solar mass. "We were really surprised by our results," says Simon White from the MPI for Astrophysics. "Everyone had guessed that the smallest clumps of dark matter would look quite different from the big ones we are more familiar with. But when we were finally able to calculate their properties, they looked just the same."

The result has a potential practical application. Particles of dark matter can collide near the centres of haloes, and may - according to some theories - annihilate in a burst of energetic (gamma) radiation. The new zoom simulation allows the scientists to calculate the expected amount of radiation for haloes of differing mass. Much of this radiation could come from dark matter haloes too small to contain stars. Future gamma-ray observatories might be able to detect this emission, making the small objects individually or collectively "visible". This would confirm the hypothesised nature of the dark matter, which may not be entirely dark after all!