Cool dense hydrogen gas around the first quasars

An atlas of the extended Ly-Alpha halos detected at around z~6 quasars (i.e., when the Universe is only 1/15th of its current age). The black dot at the center marks the quasar location. See also an animated 3D-version for P308-21 at the end of the page.

A prime objective of observational astrophysics is to peer deep into the young Universe and study how the first stars, galaxies, and black holes formed. For decades, astronomers exploited the brightness of quasars to study galaxy formation and evolution at all cosmic times, both as silhouettes against the luminous quasars, and in emission around them. Despite significant progress, we still do not understand the detailed processes whereby super-massive black holes with masses a billion times larger than the Sun assemble their mass in less than one billion years after the Big Bang, a small fraction of the current Universe age (13.7 billion years).

Hydro-dynamical cosmological simulations and analytical arguments suggest that to grow such massive systems in such a short time scale, the host galaxies of the first quasars need a continuous replenishment of fresh fuel. This gas has to be provided by cold filamentary streams from the so-called intergalactic medium down to the quasar's host galaxy and/or by mergers with other gas rich galaxies. While a merger is a violent short episode, the aforementioned filaments should be present around each quasar.

Emission from this large-scale gas is, however, typically too faint to be detected unless it is illuminated by the intense radiation from the quasar. In this case, the hydrogen in the gas reprocesses the incident radiation and shines as an extended "fuzz" of Ly-Alpha emission, now detectable with top-notch facilities. Recently, a team of astronomers from Garching, Heidelberg, and Santa Barbara took advantage of this boosted emission and embarked on a large survey aimed at uncovering the presence of this fuzz around more than 30 luminous quasars in the young Universe.

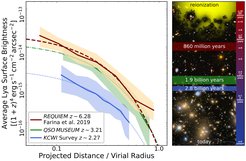

In the past years, several studies showed that quasars at the so-called cosmic noon (2-3 billion years after the Big Bang) are embedded in large Ly-Alpha nebulae. This plot illustrates how the average Ly-Alpha emission becomes fainter with increasing distance from the center of the dark matter halo where these quasars reside. The three different colors correspond to studies at different cosmic times. Surprisingly, while the shape of this drop remains similar, the earliest supermassive black holes (this study, red) appears to be surrounded by larger gas masses.

An investment of more than 50 hours with the panoramic integral-field spectrograph MUSE on the Very Large Telescope revealed that around 40% of first quasars are embedded in Ly-Alpha halos (see Figure 1) with a total extent of up to a hundred thousand light years. These halos are directly tracing the presence of cool dense hydrogen gas around the first quasars. In particular, the researchers discovered that this gas is bound within the dark matter halo of the quasar host galaxies and that it is abundant enough to maintain both the observed high-rate of gas consumption of the central supermassive black holes and their highly star forming host galaxies.

The presence of these extended nebulae is an important piece of the puzzle that astronomers are building to picture the formation of large cosmic structures more than 12 billion years ago. By providing detailed constraints on the fuel supply, these new observations can be used to test current theories and models for the growth of massive galaxies and black holes from the Big Bang to the present (see Figure 2). While additional observations are already planned to fully capture the physical status of the gas, current data already pose new challenges to theoretical models. They indicate that, rather than being smooth, "Lyman-alpha" nebulae take on the consistency of a mist comprising an enormous number of tiny droplets. Reproducing the structure of these clouds may prove to be a key challenge for the next generation of theoretical models of galaxy evolution.

3D visualization of the extended Ly-Alpha halo around the quasar P308-21 at z=6.23. The “hole” at the center represents the quasar location, which has been removed so as not to contaminate the measurement with light coming from the central black hole. The gas appears to be in a relatively quiescent motion, suggesting that it is moving within the dark matter halo where the central quasar resides.